Whatever your summer plans are, I hope you find something here to help you make the most of them.

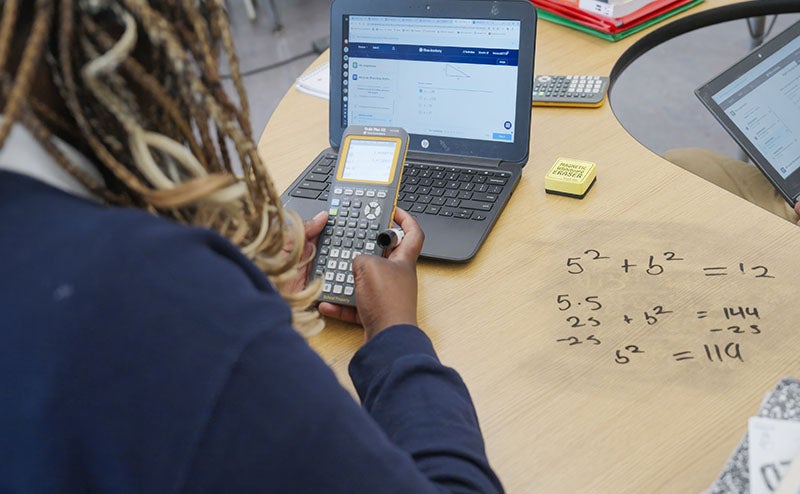

At this year’s ASU+GSV Summit in San Diego, I had the chance to catch up with Jessie Woolley-Wilson, a leader in the field of education technology and President and CEO of DreamBox Learning. During our fireside chat, we talked about the state of edtech, why math is so important for students, what the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation is doing, and the impact AI will have in the months and years ahead. Thanks to people like Jessie—and all the incredible industry leaders and educators in the room—I walked off stage feeling even more motivated about the future.

Here’s a video and transcript of our conversation:

JESSIE WOOLLEY-WILSON: It’s been some years since you and I shared a stage together, and the world has changed dramatically. Even before COVID, though, one thing that hasn’t changed much is U.S. achievement in mathematics. So we get to talk about mathematics with you today, and I’m excited about that.

But before we talk about what you’re doing in the Foundation and mathematics, I’d like to talk about Bill Gates as a kid. What made you fall in love with mathematics, and how did it impact your childhood?

BILL GATES: Well, I was very lucky. I went to a good public school through sixth grade, and then in seventh grade, my parents decided I should go to a private school. It was a great education. I developed a view that math was fun and interesting. I had very good teachers. The sky was the limit.

When I was 13, they put a computer terminal in, and the teachers found it confusing. We did not find it confusing. We took over. And then I did the school scheduling, decided who would be in what class. I put lots of great women into my classes. I never got around to talking to them, but I was planning on it.

No, I had a really, almost idyllic high school experience, including the early exposure to computers. My cofounder (of Microsoft), Paul Allen, was two years ahead of me, and he kept pushing me. Even when I went off to college, he kept saying, “We’re going to miss this opportunity.” So he moved out to Boston to encourage me to drop out, and he succeeded.

JESSIE WOOLLEY-WILSON: Well, I’d like to go ahead a few years and think about Bill Gates as a parent. You experienced mathematics through the eyes of your children. How was that experience?

BILL GATES: Well, you don’t want to try to make your kids do the same things you did. That wouldn’t be that great. They were also very lucky to get a good education. None of them were computer nerds. One of them is definitely nerdy, but more in history, science, and economics, and not math and computer science, which is probably good. They’re all way more sociable than I am, which means you inherit some from your mother, to have a more balanced personality.

Anyway, it’s been fun going through their educational experience. My eldest daughter is in medical school now. I enjoy going through those slides together and kind of learning. When things seem to have hit a dead end, young people today have more optimism for them.

JESSIE WOOLLEY-WILSON: Do you remember times when they came to you for help in mathematics as a parent?

BILL GATES: Oh, sure. I love doing math. My younger daughter would always say, “You made it so complicated,” and “You didn’t need to explain this to me to get the answer. Why did you go through that whole general description of angle, side, angle? You could have been done 10 minutes ago?” She just sort of wanted the answer.

But no, learning with kids and seeing what’s confusing to them, what’s easy for them is kind of the ultimate test of whether you know a topic—whether you can explain it. One of my favorite things was teaching calculus to the kids, because I think it’s extremely poorly taught. It’s a few very difficult concepts, like area under the curve and rate of change—you have to explain why that’s so important, and why they have those funny symbols.

But yeah, teaching is great. Even now, it turns out the latest technologies are less coding-related, and they’re more math-related. The way that you do these differentials and matrices and things like that, it’s actually pretty tough. If you didn’t come to computer programming from math, where a bunch of crazy matrix operations are second nature, then you’re going to have to go get that background.

JESSIE WOOLLEY-WILSON: I can tell that you really enjoyed math the way you talk about it.

BILL GATES: Oh, I do.

JESSIE WOOLLEY-WILSON: You’re fired up.

BILL GATES: I do. I mean, it’s crazy. It’s probably the thing I enjoy the most.

JESSIE WOOLLEY-WILSON: Do you think that when you were tutoring your kids, they were enjoying it as much as you?

BILL GATES: Sometimes. They would see that I seemed to get a kick out of it.

JESSIE WOOLLEY-WILSON: At DreamBox, our Chief Learning Officer oftentimes tells me that his kids have an advantage. When they ask him for help, they get to go to a math expert. So I think about the kids that don’t have Bill Gates for a dad, and don’t have Tim Hudson, our Chief Learning Officer, as a dad, and I think about kids who come from generations of academic underperformance and less-advantaged incomes, and therefore, not as much opportunity.

So now I want to talk about the Foundation—Bill Gates as the philanthropist and investor. Why the initiative on math out of the Gates Foundation, and why now?

BILL GATES: Well, our Foundation from the beginning was set up by Melinda and me to go after two big things. One is global health—and some things related to that, like sanitation, agriculture, and finance—and that’s ended up being the biggest thing we do. That’s the global stuff, about 85% of everything we do, and that’s gone super well.

But at the same time, our other commitment was to try and help other people have the opportunity that we’d had. Melinda had a fantastic parochial education before she went to Duke, I had my private school education, and we knew that was central to everything we’d gotten the opportunity to do.

So, we’ve been in the U.S. education space for the full 23 years that we’ve been a foundation, and we’re totally committed to the area. We’ve done a lot of different things, some of which, hopefully, people learned that those are things that don’t work. And some things have gone extremely well. Some things like scholarships, which we do a massive amount of, you hope that the trickle-down effects of those people, in terms of what they choose to do, are fairly dramatic.

But anyway, doing curriculum—and I’m defining that term in the broadest possible way—is highly impactful, because in education, there’s underinvestment in R&D, in really understanding why some teachers are twice as good as other teachers, and where technology can really come in and help.

The over-optimism about the impact of technology is constant. We may overstate its potential, even at this conference once or twice, given the number of elements that go into successful education. But how little research was done on great teachers and good learning experiences was kind of a stunning thing to me.

And so our Foundation is one of many that have funded a ton of things—charter school things, and we do a lot of higher-education, but K-through-12 is very important for us. We are now shifting a substantial percentage of our resources into math. With math, there’s not that much R&D or philanthropic money going into math. It is a sort of necessary foundational skill. The income- or race-related inequity related to math is very dramatic.

We actually made this strategy shift before the pandemic came along. So it’s not a post-pandemic thing—although, as you look at the numbers of how much people have fallen behind, and how that also has an equity tilt to it, we feel very good that here we are, contributing to the understanding of what type of engagement in and out of the classroom leads to competence and persistence in basic math skills.

JESSIE WOOLLEY-WILSON: When we think about the last 10 years, maybe even 20 years, we think about all the changes and all the investments that we’ve made—with a lot of optimism—in things like curriculum, technology, school models, pedagogy. So much change. And yet, mathematics remains a stumbling block for many, many kids, especially the least well served.

What is the Foundation going to do differently? You’ve talked to me a little bit about motivation, engagement, and persistence. Can you tell us a little bit about why that’s so important to you?

BILL GATES: Well, I’m sure there’s broad agreement that all learning things have a huge motivational element to them. If you’re insanely motivated, let’s say, to learn physics, just read Feynman’s books. It’s all there. It’s not like somebody’s putting something online that’s some new discovery of how physics works. It’s just very hard to maintain that type of mental concentration, and you have to have a reason for doing it.

And one thing I even feel a little guilty about in my math education was that I viewed it as a contest to be faster than the other kids and make it look like, well, I don’t have to try at all. You know, I would never take the textbook home. I would always leave it on my desk, like, hey, I don’t even need to look at this thing. If I needed to, I cheated and bought another copy of the textbook at home.

I bet you I discouraged probably 50 kids from trying to do math because they knew, as long as you were in math classes, there’d be some person like me, not reinforcing your success necessarily.

It’s very easy to check out from math. And it’s very easy to think, “Okay, I’m not going to be a scientist, so I don’t need it,”—whereas a lot of math is about understanding the world, particularly now with so much data and statistics. The world and these subjects are super-fascinating, even for understanding our tax system or income distributions or sports variants.

If you don’t know math, you won’t really appreciate the beauty of all these things.

The motivational piece of: “Can I succeed here? Am I glad I’m in this classroom? Is it worth paying attention?”—that, which we see across all subject domains, is probably most acute in math. You even see it in adults when they know they’re out of practice, and they’re not very anxious to get into a question that involves doing even pretty standard mathematics.

So, we have to understand how to really change that classroom experience, with things like growth mindset, things like engagement and struggle, making it a social experience. There are so many promising things in mathematics.

A lot of what we have to do is, through teachers in the classroom, see how we assemble the mix of inquiry, direct instruction, homework to achieve a sense of success. Because we need, through the curriculum and professional development, something far better than we have.

There certainly are things that are helpful. Tools like DreamBox—which is more than a decade of persistent work, and seeing what works and how do you get people to adopt these things? There are good ideas, at least in the abstract, like a personnel system where you really tell teachers how to work better, that when we’ve tried to actually implement them, they essentially get rejected.

And so what works abstractly and what ends up working in terms of scale in education are different things. You often get fooled that you do things, and you happen to have picked particularly talented teachers, and so no matter what you do with them, when you say, "Here’s the money, go do X," then they’re like, "Hey, kids, we’re going to do X, and let’s see if we do better because we’ve been picked, and it’s very important," and you always see some improvement there. But then when you take it to teachers who don’t want to do X, it doesn’t necessarily scale up.

So education—for the entire Foundation and for me, personally, given the difficulty of having impact at scale—turned out to be harder than I expected. Whereas weirdly, our global health work, where I thought it would be hard to have impact at scale, it turned out it was actually pretty easy to have impact at scale.

JESSIE WOOLLEY-WILSON: That’s very interesting. When we were chatting earlier, you were talking to me about three Cs. You didn’t say three Cs. I said three Cs so that I could remember it. One was confidence, one was curiosity, and one was constant feedback, and the importance of all three Cs in learning.

You also said something very interesting, and I found myself reflecting on it. You said, "We have to resuscitate curiosity." What does that mean to you, to resuscitate curiosity?

BILL GATES: Well, in math, what it means is that you can say, "Look, I’m not good at that stuff … that stuff just sort of doesn’t make sense … it doesn’t come together." And you know, I’ve sat in at the college level, in a practice that we’ve pushed against, which are these developmental education courses. When you get admitted even to community college, if the math practice test that you take scores you at a certain low level, then this math course becomes a blockade, and you can’t even start your nursing or policing career, or whatever aspiration you have, until you pass this math course.

And I’ve had the experience of going into that course and seeing kids, and they’re just like, "Oh, no, here’s this thing again. These funny symbols are going to come up on the board," and one of the most gifted teachers—we were down in Florida, at Miami-Dade Community College—and the teacher was saying, "Hey, we’ve all been told we’re not good at math."

And so she chose to very directly address the idea of mindset, that you’re discouraged and that you don’t even really want to be here. She knows these kids probably won’t walk out and be laughing about, "Wow, that is so fascinating, what I learned about X and then Y and then Z, and who would have guessed how amazing the quadratic equation is? I’m going to tell my friends later tonight."

JESSIE WOOLLEY-WILSON: Somehow, I don’t think you’re making this story up.

BILL GATES: But it’s so indirect, the payoff, unless you’re careful. Now, some really good math curriculum is taking things like variants or causality, and there are some best practices. But you’ve got to know that getting people’s attention is critical—their rate of learning will be relative to how much they’re paying attention.

If you just put a camera, and you point it not at the teacher but just at the class, and you looked at what’s going on—we did this early on in the Foundation, where we filmed teachers who got very good success and teachers who did not and tried to understand those exemplars, and we had cameras facing both ways—you could predict who the good teacher was, without any sound, or without seeing the teacher. You just look at the video of the classroom and see if the kids were paying attention or not. And although some direct instruction is very, very important, there’s a limit, particularly in math, of how much people are just going to sit there and give you their attention.

So all these tools—it seems like a gimmick in a way, but creating the relationship with the teacher, creating that group environment—there are efforts to get it to be a positive experience where people will find themselves fascinated and curious. And even people’s initial insights about a problem, if you can praise those, when they are headed even slightly in the right direction, that’s part of this resuscitation.

JESSIE WOOLLEY-WILSON: So it’s not lost on me that we sit here with a lot of experts and a lot of investors in education technology. And what you and I are talking about isn’t very much about technology. What you’re talking about right now is so hard, this mindset change.

So one of the things we tried to do at DreamBox is make sure that people believe—that students and teachers and administrators believe—that every child has the capability to learn mathematics. And that’s one of the hardest things that we do, to change that mindset.

So we go out of our way to go to less-advantaged populations where people don’t expect excellence: Compton Unified, William Penn. We just launched results today from the state of South Carolina, not Massachusetts, not New York, but South Carolina, with 77,000 fourth and fifth graders who are excelling in mathematics.

It’s wonderful research. They’re going to outperform the state expectations 3X for the underprivileged, and 2X for those that are achieving. At 77,000, that’s not a fluke. We hope to change belief systems, and therefore get that shift.

What can the Foundation do to help shine a light on excellence in places that people don’t expect?

BILL GATES: Well, efficacy studies, which we could talk about a lot, in terms of whether what we expect for them is sometimes too high. But the amount of evidence in education is stunningly low. When you go to that Department of Education thing, and you say, "Okay, what has really strong evidence?" I think it’s like DreamBox and just a few others.

And that’s really weird. Why is it so hard? Why don’t we have more variety of evidence that’s helpful?

Certainly in mathematics, the idea of capability is measurable. At the end of the day, yes, you have to go through motivation, engagement, interactivity—but at the end of the day, do I have numeracy? Do I understand fractions? That is knowable. It’s easier to know than, let’s say, is my writing output very, very good? And okay, what feedback should I get? Where are the flaws in my mental image of doing writing?

So math, I would have thought, “Okay, wow, as soon as they have the ability to do infinite amounts of practice, at least persistent students will.” But it turns out that’s a very, very small percentage. And so amazing tools like Khan Academy—although they’re super wonderful and now they are getting into the classroom and everything—those were at first more tools to help people like me to just do more problems than that kid that I had discouraged. Believe me, he wasn’t going home at night and logging in for more punishment.

So part of this missing R&D money is to fund really high-quality studies and make sure that they’re done well. And there’s many pieces in mathematics. There’s core, supplemental, assessment, all these things—we not only need to test those pieces, but we need to test how all those pieces come together. And a lot of the mindset stuff, some people think of it separately, but you have to integrate that, and you have to get that into the teacher training.

Even once we have great curriculum, a lot will depend on the professional development, the quality of that, and the seriousness of how well that’s done. Otherwise, the natural variation will defeat you as you’re trying to scale it out.

JESSIE WOOLLEY-WILSON: That evaluation is super hard, though, right? These large-scale, random-control trials take a lot of time, and they have immeasurable opportunity costs on some students. You have to have students in a control group, and it’s really hard to look at an administrator and say, "Take these students, and give them nothing. And then take these students so that you can do a test."

So the evaluation is a challenge. It’s a challenge for investors to try to figure out what’s worthy of a marginal dollar of investment. It’s challenging for companies who want to partner with schools. And it’s super-challenging for administrators as they try to cull through all the stuff that they have to figure out what they should keep in and what they should get rid of.

Before COVID, there were about 600 education technologies in the average district. Post-COVID, it exceeded 1,400. But now, a lot of school districts are saying, "What did that investment get for me?" And they have to figure out what to get rid of and what to double down on.

And so it’s great, I think, that the Foundation is trying to figure out how to create some research tools to help facilitate that decision making and give them rubrics. I think that’s fantastic.

JESSIE WOOLLEY-WILSON: So let’s talk about Bill Gates, the futurist. There have been a lot of sessions during the last couple of days here about AI. In fact, most people couldn’t get in. They were standing room only, and there were a lot of frustrated people out there.

You and I were talking about AI and the impact you think it could have on learning and on mathematics in particular. Can you share what your thoughts are about the promise of AI—in mathematics in particular, and in general?

BILL GATES: AI, ever since the focus became machine learning, has achieved some unbelievable milestones. It can listen to speech and recognize speech better than humans. It can recognize images and videos better than humans.

The area that it was essentially useless in was in reading and writing. You could not take, say, a biology textbook, and read it and pass the AP exam. Now, you could regurgitate the biology textbook, but in no sense would you call that understanding, or the ability to read and encode the knowledge in a kind of semantic way.

There were these debates, as we scaled up large language models, about how much emergent richness would come out of that. I was actually one of the people who didn’t think as much would come out of it. Even when I looked at GPT-3, I was like, "Nah, it still must have some upper bound there."

It was last summer that I challenged the OpenAI Microsoft group. I said, "Hey, when you can pass the AP biology exam, bother me, but in the meantime, I’m going to work on malaria and TB and HIV, because I’m not sure.” And you know, a few months after I said that, they then came to me. We had this big dinner where they showed it not just barely passing, and not just, "Oh, I guess that’s a good answer," but blowing the questions away. There were a few that it didn’t get right, that later we learned had to do with certain types of very abstract reasoning, including mathematics.

And so the breakthrough we have now, which is very recent, has more to do with reading and writing, this incredible fluency to say, “Write a letter like this, write a letter like Einstein or Shakespeare would have written this thing,” and to be at least 80% of the time very stunned by it.

The impact on sales jobs, service jobs is phenomenal—and we can say that just based on the version we have now. And yet, the amount of money going into making these things better is absolutely gigantic. It’s not just GPT-4. It’s hundreds and hundreds of companies building competitive things and building on top of it.

I’d say in mathematics now, one danger is that people think that all the stuff we’ve been working on, like DreamBox, is somehow obsoleted by this, which is absolutely not the case. We are on that long journey, and those tools, put into the right mix in the classroom, are very, very important.

It’s really about the blend. How much time do you have with the student, and how quickly can they learn various things. Sometimes people will take one little piece and say, “Okay, that’s the whole thing.” But it’s actually that blend.

AI is going to help with math—the ability to understand mental misconception, the ability to give you very quick feedback in an even deeper way than today’s systems do—but I wouldn’t say that it immediately helps with the motivational piece. We don’t yet have the personal tutor. The gold standard of learning basically is a personal tutor who’s looking at your fatigue and your interests and constantly adapting. Because when you have one student, that’s a lot easier to do. The AIs will get to that ability, to be as good a tutor as any human ever could. We have enough sample sets of those things being done well that the training can be done on it.

I’d say that is a very worthwhile milestone—to engage in a dialogue where you’re helping students understand what they’re missing—and we’re not that far. We don’t have that yet today. There’s pilots of these things, like the Khanmigo stuff. It’s a great collaboration that goes back to last fall, right at the time that the new breakthrough took place. Khan Academy was one of the partners brought in at the very beginning.

JESSIE WOOLLEY-WILSON: When we were chatting, you mentioned—kind of as a joke, but it was true—that ChatGPT can’t multiply. So you wanted me to be cautious about what could happen in the short term in mathematics.

BILL GATES: It’s stunning. The way we do these embeddings, if you look at how numbers get embedded, there is no semantics associated with number embedding. There’s mind-blowing semantics associated with word embeddings. Words work in a group to create sentences. Sentences create paragraphs, and things like that, and you have very deep meaning. Sets of numbers are truly arbitrary. All those numbers are possible. So there’s no inference that you make by saying, “Oh, I saw this number, I saw this number.” It’s not like you think, “Oh, well, that means you never use this other number.” No, it’s a continuous set.

Actually, not a day goes by that I’m not exchanging mail with Microsoft and the other AI people saying, “Look at this math problem that it can’t do, and why is it?” The current mechanism in terms of reapplying rules an arbitrary number of times, like you do when you’re simplifying a math equation—it doesn’t have any sense of how hard to work on something. It spends exactly the same amount of computation on every token it generates. And it doesn’t know that a problem is important or unimportant.

And that’s one of the things, that sort of meta model of reasoning, that over the next year the leading AI implementers will be adding. The thing will get good at math. But there are some really stunning things, including multiplying, that do not fall out of a generative model.

JESSIE WOOLLEY-WILSON: I want to talk a little bit about equity within this frame of AI. It seems to me that technology now in learning is really in the realm of tools. We use technology tools to help us do things that we currently do better, faster, even with more personalization.

With AI, it seems to me technology is going to transition to more of a collaborator with the student, not a tool that the student uses, but a collaborator with the student. And so, what the student does when they interact with AI technology is going to be about how to query, how to prompt the system to try to get to the answer or the information that they want. That’s going to translate into different skills that we collectively need to cultivate in the next generation of learners.

And so, if these powerful technologies are in the hands of the “haves,” and those haves are starting to understand how to prompt and query and discern the difference between something that’s presented authoritatively and something that’s actually factual, for example, and there are large numbers of students who are not learning those next generation skills, I wonder what the impact on the gap between the haves and have-nots is. I wonder what’s going to happen to that gap, and I wonder about the impact on society and how we live.

BILL GATES: Well, I think overall, the marketplace is always going to take the latest technology and make it available to the people who can pay high prices for it. It’s the role of governments, at least within their own country, and philanthropies on a global basis to take that and offset that.

Fortunately—although the backend execution has some expense associated with it, and the demand is going up so high that for the next couple of years, there actually will be some bottleneck in that execution capacity—over time, through both hardware and software improvements, the cost of this stuff will get very low. And a lot of it will move down to be client-based. It’s not like an expensive chemotherapy, or access to a very trained doctor, which you can’t scale down.

The whole purpose of an entity like the Gates Foundation or many others will be to make sure this gets used on an equitable basis. For us, therefore, the two domains of great interest are health and education. And over the last six months, I’ve been to so many long meetings where we brainstorm, “Okay, what does this mean for drug discovery for diseases of the poor? What does this mean for health consultations in Africa, where most people live their entire life without meeting a doctor?” It’s not that they only meet a doctor rarely; they never meet a doctor. So many different conditions simply can’t be diagnosed, and we can revolutionize that. And the cost of doing it won’t require some unrealistic amount of financing.

So overall, in health and education, this should be a leveler. Because having access to a tutor is too expensive for most students—especially having that tutor adapt and remember everything that you’ve done and look across your entire body of work.

I think at first, we’ll be most stunned by how it helps with reading—being a reading research assistant—and giving you feedback on writing. Writing has been tough. What a good teacher does is take your essay and mark it up and say, “Oh, this isn’t clear, and the summary should have included this.” That is a high cognitive exercise, and software, except at the really trivial kind of grammar level, has had essentially zero—there’s been a little bit of work but not that much—benefit. Particularly once you get out of a very templated writing exercise, the amount of feedback to help me improve my writing is very low and these AIs actually are good at that. That is what this sort of word-guessing-game emergent behavior is: incredible fluency at being able to read and write.

If you just took the next 18 months, the AIs will come in as a teacher’s aide and give feedback on writing. And then they will amp up what we’re able to do in math. Our bottleneck in math really is more of how we fit in the overall system and getting that teacher adoption. We have very good tools today, that if they were fully adopted, would actually make more progress in math scores than we’ve made in the last 20 years. So my optimism about edtech in general is not just because of AI. It is a set of things, even before this latest advance, that I think we’re getting smarter about and getting out into the field.

JESSIE WOOLLEY-WILSON: You mentioned there’s a special role for government and philanthropy. And investment is really about choices. There’s a lot of conversation at this conference right now about investing in AI. And a lot of investors here—VCs, PE firms, seed investors—are trying to find out where they should put their investment, especially after the year we all had last year. What advice might you give them about being among the first, the innovative class, that’s going to explore a lot of things, experiment in a lot of ways, and find a lot of failure while we learn, versus maybe having edtech be a fast follower to what’s happening in other industries, so we don’t incur the opportunity cost of what you just spoke to? There are a lot of things that are working now, and if we could just get them working at a higher fidelity, we could actually have a bigger impact on learning outcomes, especially for marginalized students.

BILL GATES: Well, from a pure trying to make money point of view, I don’t envy anyone out there. This is internet 1999, 2000, 2001, where the number of dead ends is going to be super impressive. Some of these things are very scale-oriented, where the R&D budget of Google, the R&D budget of Microsoft plus OpenAI. There are certain aspects of this that are more platform-ish, scale-oriented.

Now, there may be a few that completely surprise everybody and rise to be the next Google or Microsoft based on their AI advances. But I guarantee you, it won’t be more than two out of a thousand. And it could be zero, honestly, in terms of the base technology.

One of the pieces of good news, though, is that all the companies involved in this—certainly the big companies like the partnerships you hear about—are super interested in having it be used in education. Even if you can’t recover the backend costs for executing these things, there’s a desire for AI to not just be a productivity thing—and I’m big fan of improved productivity. But education and health are the two things that, even in internal meetings, everyone’s talking about, “Okay, how do we partner up on these things, how do we get these things going?” So the interest level and making it available, and to have this be the first technology that even in its first five years has a meaningful benefit in education, I’d say that is super strong.

And so, the practitioners here who have sat in classrooms understand how you get adoption. Seeing the magic that this software can now perform—particularly for reading and writing things, but within the next 18 months for math as well as we fix some of these limitations that the system has—I am really quite optimistic that the field of education will improve.

For the investor to figure out “Okay, which one of these things.” Making money in edtech has never been like some dream easy thing to do.

JESSIE WOOLLEY-WILSON: Shhh!

BILL GATES: Okay, fine. Keep investing. And I won’t tell you it’s philanthropy, but some of it might end up being philanthropy. At least I’m not confused when I spend money on edtech.

That’s being a little flippant, so I really want to say the truth, which is: Things that are just philanthropically funded also have a huge problem, unless you get them into a company that wakes up every day trying to figure out, “Okay, how do you get adoption?”

So both models, the pure, “Hey, let’s just make money,” where the R&D tends to get cut down a lot and it becomes very sales oriented, and the “Hey, it’s just pure philanthropy, oh, look, our technology is really good,”—trying to get the best of both worlds is a necessary thing.

JESSIE WOOLLEY-WILSON: I stand corrected.

BILL GATES: Yeah, absolutely, I didn’t want anybody to summarize, “Hey, he doesn’t believe in private sector incentives for educational technology.” Because in the end, that is the most important thing that will pull all this together into full solutions.

JESSIE WOOLLEY-WILSON: So why don’t we end on Bill Gates, the humanitarian. As you look out 10 years, what will give you a sense of satisfaction and hope about the future of humanity, as you think about where we are now in education, and where we’ll be in 10 years?

BILL GATES: Well, certainly, humans are good at worrying, and we’ve given them plenty to worry about.

JESSIE WOOLLEY-WILSON: Climate change.

BILL GATES: Yeah, we’ve got climate change. We’ve got polarization, populism. We’ve got a war that somewhat involves countries with nuclear weapons. And so, it can feel a bit challenging.

I will say, though, on the innovation side and on the health side, the edtech side, the climate side, the pace of innovation—even before you get to AI—is much faster than I would have expected. And a lot of that is great universities in the United States, great companies in the United States. The startup mechanism, even now that valuations have come down a little bit, the amount of money for that great work is incredible.

And so, when I look at every area of emission in climate, there are great companies out there. My Breakthrough Energy is in over 100. I’d say there’s over 200 that are doing really amazing work. Likewise in health, in the rich world, which I’m not directly involved with, there are things like obesity and cancer and even aging where the progress is pretty phenomenal.

In the Foundation realm, having a genetic cure so that you don’t have HIV, or you don’t have sickle cell—we see a path, a decade-long path, to bring that down to be only a few thousand dollars instead of millions of dollars that we have today.

So I’d say human ingenuity is going to surprise us on the upside. The messiness of getting these things into the world, the real world—a world with populism and tough geopolitical tensions—it’s always going to be interesting, and there will be gigantic setbacks, including things like the Ukraine war.

The next decade for the very poorest countries, where their finances are in tough shape, won’t see as much progress as we’d like. But because of ingenuity and innovation, I do think the poor countries will have a lot of catch-up over time. And even our dreams about education, even though they’ve taken a lot longer than we hoped for, that we’ll be able to achieve them.

JESSIE WOOLLEY-WILSON: Well, Bill Gates, thank you for sharing your aspirations and your intentions and your wisdom with us. It’s my pleasure.

BILL GATES: Thank you.