Global health is now rightfully seen as a serious national and global security issue.

I’m a longtime fan of Comedy Central’s The Daily Show. When Jon Stewart stepped down as host in 2015, I was sad to see him go. I was also worried for his replacement, Trevor Noah, a South African comedian. Stewart’s style is so unusual that I didn’t see how anyone could fill his shoes—especially someone like Noah, who describes himself as an outsider. As popular as Noah was in South Africa, I didn’t know whether his humor would connect with American audiences.

I’m happy to report that I was wrong. Millions of viewers—myself included—are tuning in to The Daily Show because Noah’s show is every bit as good as Stewart’s. His humor has a lightness and optimism that’s refreshing to watch. What’s most impressive is how he uses his outside perspective to his advantage. He’s good at making fun of himself, America, and the rest of the world. His comedy is so universal that it has the power to transcend borders.

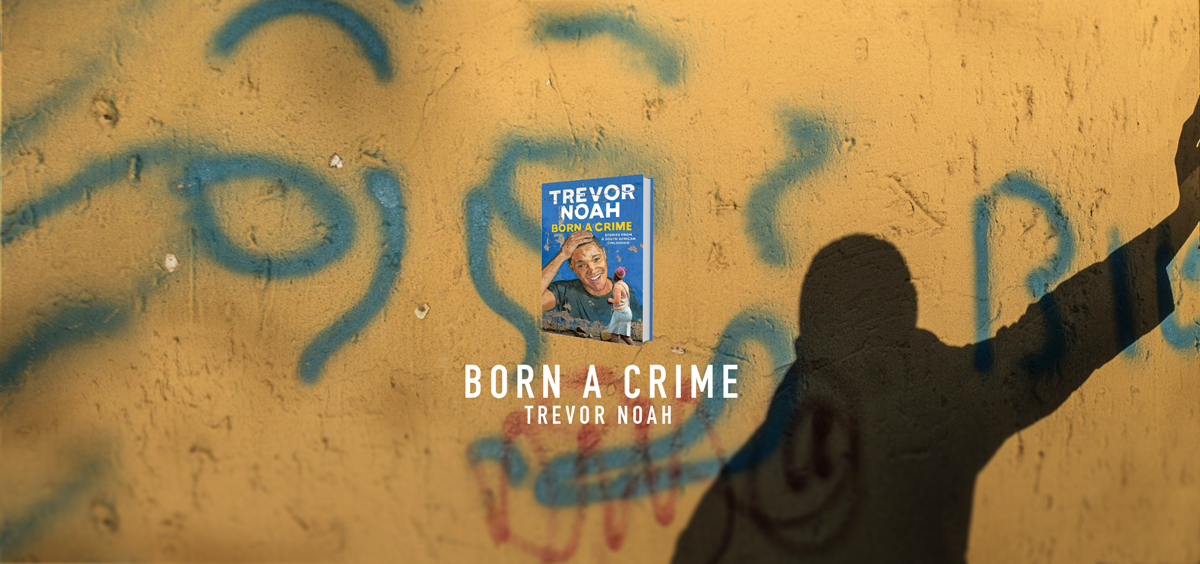

Reading Noah’s memoir, Born a Crime, I quickly learned how Noah’s outsider approach has been honed over a lifetime of never quite fitting in. Born to a black South African mother and a white Swiss father in apartheid South Africa, he entered the world as a biracial child in a country where mixed race relationships were forbidden. Noah was not just a misfit, he was (as the title says) “born a crime.”

In South Africa, where race categories are so arbitrary and yet so prominent, Noah never had a group to call his own. As a little boy living under apartheid laws, he couldn’t be seen in public with his white father or his black mother. In public, his father would walk far ahead of him to ensure he wouldn’t be seen with his biracial son. His mother would pose as a maid to make it look like she was just babysitting another family’s child. On the schoolyard, he didn’t fit in with the white kids or the black kids or the kids who were “colored” (the term used in South Africa to describe people of mixed race).

But during his childhood, he quickly discovered that there’s a freedom that comes with being a misfit. A polyglot who speaks English, Afrikaans, Xhosa, Zulu, Tsonga, Tswana, as well as German and Spanish, Noah used his talent for language to bounce from group to group and win acceptance from all of them. One of my favorite stories in the book involves Noah walking down the street when he overhears a group of men speaking in Zulu about how they were plotting to mug “this white guy.” Noah realizes they were referring to him. Noah spins around and announces in perfect Zulu that they should all mug someone together. The Zulu men are startled that Noah speaks Zulu and a tense situation is defused. Noah is immediately accepted as one of their own.

Again and again throughout his childhood, he discovered that language was more powerful than skin color in building connections with other people. “I became a chameleon,” Noah writes. “My color didn’t change, but I could change your perception of my color. If you spoke to me in Zulu, I replied to you in Zulu. If you spoke to me in Tswana, I replied to you in Tswana. Maybe I didn’t look like you, but if I spoke like you, I was you.”

Much of Noah’s story of growing up in South Africa is tragic. His Swiss father moves away. His family is desperately poor. He’s arrested. And in the most shocking moment, his mother is shot by his stepfather. Yet in Noah’s hands, these moving stories are told in a way that will often leave you laughing. His skill for comedy is clearly inherited from his mother. Even after she’s shot in the face, and miraculously survives, she tells her son from her hospital bed to look at the bright side. “’Now you’re officially the best-looking person in the family,’” she jokes.

“If my mother had one goal, it was to free my mind.”— Trevor Noah

In fact, Noah’s mother emerges as the real hero of the book. She’s an extraordinary person who is fiercely independent and raised her son to be the same way. Her greatest gift was to give her son the ability to think for himself and see the world from his own perspective. “If my mother had one goal, it was to free my mind,” he writes. Like many fans of Noah’s, I am thankful she did.