I’m glad that smart writers like Elizabeth Kolbert are reminding us of the risks of trying to intervene in nature.

When I was a student, I was lucky to have some inspiring teachers—including a wonderful librarian when I was in the fourth grade and a chemistry teacher in high school—who challenged me and brought out my best. They helped make me the person I am today.

I recently met a remarkable teacher who is doing the same thing for kids who face obstacles I never could have imagined when I was in school. Her name is Mandy Manning and she teaches English and math in Spokane, Washington, to immigrant and refugee teenagers who have just arrived in the United States. They come from all over the world: Syria, Guatemala, Afghanistan, Myanmar, Sudan, Mexico, Tanzania, even Chuuk State. They show up at school speaking little or no English. Some have fallen far behind in other subjects after months or years of living in refugee camps. Mandy is the first teacher they encounter in this country.

In recognition of her work, Mandy was named Washington state’s 2018 Teacher of the Year. She also had the big honor of being named National Teacher of the Year for her efforts to “help her students process trauma, celebrate their home countries and culture, and learn about their new community.” Like other recent Washington teachers of the year (see here, here, here, and here), she was nice enough to visit my office so I could learn more about her and her students.

Mandy teaches at Ferris High School’s Newcomer Center, which was created in 1997 specifically to help immigrant and refugee students make the transition to living in the U.S. I’ve been going to Spokane for years to visit relatives there, so I know a bit about the city, but I was surprised to learn how diverse the student population is. Mandy told me 77 different languages are spoken in the district. It’s not unusual for her to have a class with 12 students who speak eight different languages.

“A lot of the kids have come through trauma to get to the United States,” Mandy told me. “They've faced war, extreme poverty, religious and political persecution, the loss of family members. And it’s not automatically the land of milk and honey when you get here. They have days where they’re struggling with culture shock or post-traumatic stress. Now it’s gotten a little bit worse because people feel more empowered to say really hateful things.”

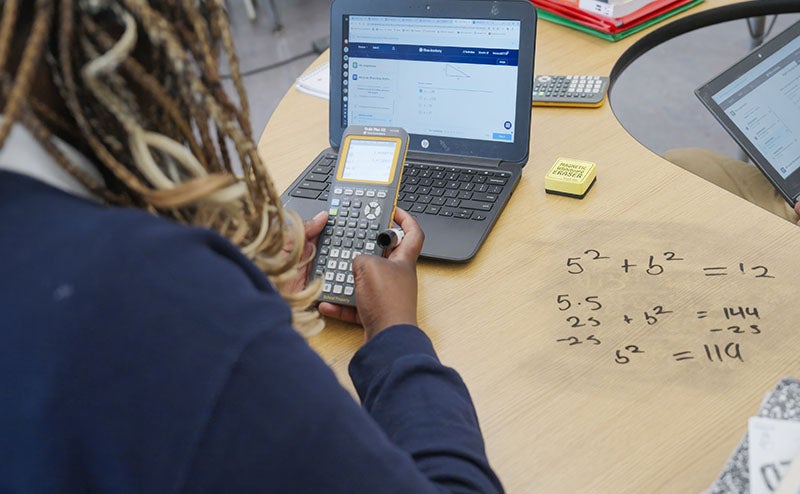

Even so, Mandy says her students are “innately hopeful, because they came out alive.” “The kids are so excited to be in school,” she said. “It’s a moment in their day where they know what is expected.” They’re generally at the Newcomer Center for one semester before transitioning to Ferris or one of Spokane’s other high schools. They spend five periods a day with Mandy, learning English and math, and one period with another teacher working on basic computer skills like how to use software and navigate a website. They interact as much as possible with their peers at Ferris High, going to pep rallies and sporting events and staffing the student store. It’s a great way to make friends, practice their English, and get to know their new community.

Mandy shared some of her students’ unforgettable stories. She told me about a 14-year-old Sudanese girl who arrived at the Newcomer Center in 2012 after spending much of her life in a refugee camp in Kenya. The girl had a fourth-grade education and spoke very little English when she arrived in Spokane. But through a ton of her own hard work and support from her teachers, she graduated from high school in four years. Today she’s enrolled at a university here in Washington state, where she’s studying to be an elementary school teacher.

I hadn’t met many National Teachers of the Year before, so I asked Mandy what that’s been like. She’s not in the classroom this year—instead she’s visiting schools and talking with educators across the country. She compared it to the time she served in the Peace Corps in Armenia. “It’s mostly about cultural exchange,” she said. “I bring back what I learn, and they hopefully have learned a little from me.”

In addition to listening and learning, Mandy is using her platform to champion ideas about education that she has developed in her 19-year career. She’s a big advocate for making sure kids see how their classes are relevant to their lives; she said when that happens—when you’re really engaged by your studies— “you can be a time traveler, seeing yourself in the future going to a university.” She is also calling attention to the disparities between high- and low-income schools. And she argues persuasively that teachers need more of a voice in setting education policies. (She wrote an excellent post here on TGN on that point.)

Hearing Mandy talk about her students reminded me of one of the biggest strengths of America’s public schools: They are intended to help every child succeed. The fact that some places fall short of that ideal should not obscure the successes that are happening in Spokane and other cities across the country. And behind every one of those successes are super-talented, hard-working teachers like Mandy Manning.