Hannah Ritchie provides tangible action that people, companies, and governments can take to build that better world—one where trade-offs between human well-being and environmental protection, between life today and life tomorrow, no longer have to be made.

Two of the things I love most about my job are getting to see amazing innovations and talk to remarkable people. During a recent trip to New York, I got to check both boxes. I met a woman named Papa Blandine Mbwey who is using a revolutionary new invention to help more kids get vaccinated.

Blandine has worked as a vaccinator in a remote part of the Democratic Republic of the Congo for over a decade. Most days, she travels on foot to villages all over her region so she can vaccinate kids who live too far from a health clinic to make the trip themselves.

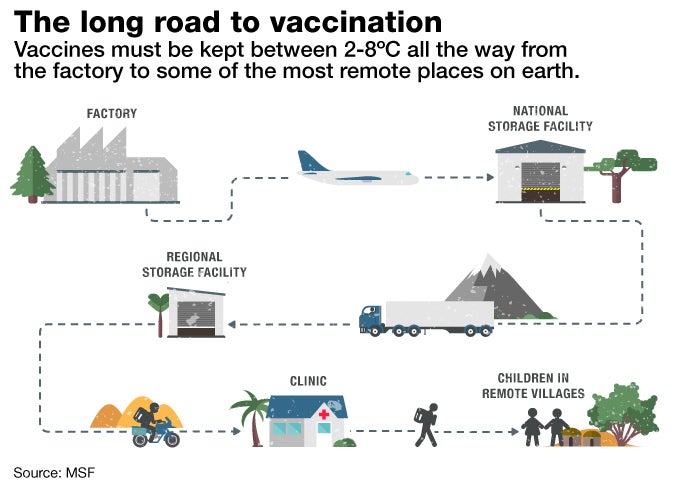

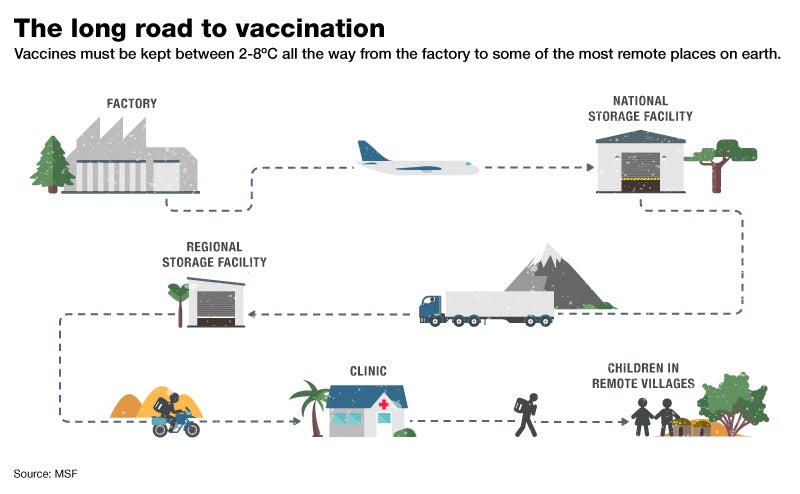

Blandine’s job is complicated by a simple fact: vaccines must be kept between 2 and 8° C. If they get too warm, they spoil. If they get too cold, the water in them freezes, and they can stop working. Vaccines must stay within this temperature range through each step of what’s called the “cold chain.”

By the time Blandine reaches the children, the vaccines she’s carrying have traveled nearly 5,100 miles. They could have spoiled at any point during that journey, but vaccines are particularly at risk during the last two stops.

First there’s the health clinics where vaccinators like Blandine usually pick up their supply of vaccines. Many of these clinics are in areas with frequent power outages or no electrical grid at all, which means the refrigerators can’t always keep the vaccines cold.

But even if the vaccines survive the clinic, they still need to make it to the children. Most vaccinators carry them in ice-lined coolers. If you’ve used a cooler to keep your drinks cold at a picnic, you know the big problem with ice: it starts melting as soon as you take it out of the freezer. This means that some of the kids never get vaccinated, because coolers can’t keep vaccines cold long enough to reach them.

Several years ago, I asked a group of inventors called Global Good that I support to take on the cold chain problem. They came up with two remarkable innovations that are changing the game for vaccinators like Blandine.

The first is the MetaFridge. Although it looks like a regular refrigerator, MetaFridge has a hidden superpower: it keeps vaccines cold without power for at least five days. The electrical components are designed to keep working through power surges and brown-outs. During extended outages, an easy-to-read screen tells you how much longer it can stay cool without power so health workers know when to run a generator or move vaccines elsewhere. And if the fridge stops working properly, it transmits data remotely to a service team so they can fix it before vaccines are at risk of spoiling.

The other innovation Global Good invented is the Indigo cooler, which is the device you see Blandine using in the video above. It keeps vaccines at the right temperature for at least five days with no ice, no batteries, and no power required during cooling.

It sounds counterintuitive, but the Indigo needs heat before you can use it. When exposed to a heat source, water inside its walls evaporates and moves into a separate compartment. It can then sit on a shelf for months after heating, ready for use.

When it’s finally time to head out to the children, you open a valve, and the water starts moving back where it started. Because the pressure inside the Indigo has been lowered to the point where water evaporates at 5° C, the water particles take heat with them (the way sweating lowers your body temperature) and cool the storage area down to the perfect temperature for vaccine storage.

Both inventions are already making an impact in the field. A Chinese manufacturer started selling the MetaFridge last year, and a new solar-powered version will hit the market soon. One of the biggest surprises so far is just how much we’ve learned from its remote data monitoring capabilities. We knew the electrical grids in sub-Saharan Africa were unreliable, but we now know exactly how much the power fluctuates. This information will be helpful moving forward for health providers and anyone designing a product meant to work in these areas.

The Indigo is in the field trial phase. It’s still early, but the data suggests that the Indigo is allowing vaccinators to reach four times as many places as they could with the old ice-based coolers. That’s a big deal, and I’m excited to learn more.

Keeping vaccines cold when you’re delivering them to the most remote places on earth is a tough problem—and these devices show how innovation can help solve tough problems. I hope MetaFridge and Indigo inspire other inventors to find creative solutions.