Something remarkable and all too rare is happening in Flagstaff at NAU:

The school is redefining the value of a college degree

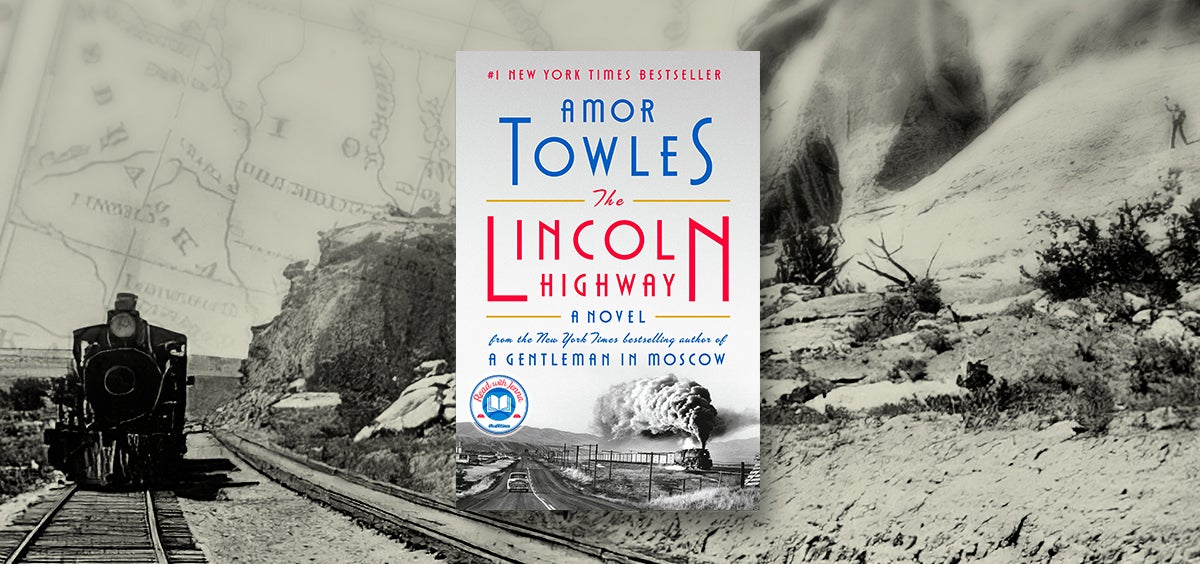

Whenever I choose a novel and put it in my canvas book bag, I optimize for great storytelling—almost regardless of the topic. One of my new favorite storytellers is the writer Amor Towles. In 2019, I reviewed his book A Gentleman in Moscow, which was fantastic. So it was a no-brainer to pick up his next novel, The Lincoln Highway, when it came out last October.

Once again, I was wowed by Towles’s writing—especially because The Lincoln Highway is so different from A Gentleman in Moscow in terms of setting, plot, and themes. Towles is not a one-trick pony. Like all the best storytellers, he has range.

The title of this latest book refers to America’s first cross-country roadway for automobiles, which stretched from New York City to San Francisco. The story takes place over ten days in 1954, when two young brothers, Emmett and Billy, intend to drive their Studebaker from Nebraska to California. (I could picture the car clearly—my dad had one too.) But fate, in the form of a sympathetic but volatile character named Duchess, forces them to travel in the opposite direction before they can have a chance to start fresh in the West.

Towles takes inspiration from famous hero’s journeys, including The Iliad, The Odyssey, Hamlet, Huckleberry Finn, and Of Mice and Men. He seems to be saying that our personal journeys are never as linear or predictable as an interstate highway. But, he suggests, when something (or someone) tries to steer us off course, it is possible to take the wheel.

My favorite character is Billy, an eight-year-old who has endured abandonment by his mother and the death of his father. At the beginning of the story, when Billy’s brother, Emmett, returns home after 15 months of juvenile detention, Billy comes across as a sweet but hapless dreamer who has survived by escaping into adventure stories. By the end of Billy and Emmett’s journey east, it’s clear that Billy is anything but a tragic figure. He is amazingly clever and resilient. In that way, he reminds me of Nina, the precocious nine-year-old from A Gentleman in Moscow.

Emmett also seems like a tragic character early on. He has the tragic flaw of anger: His juvenile detention was the result of punching (and inadvertently killing) a bully who was taunting him. But Emmett finds ways to overcome his temper.

Another hero is Sally, a young neighbor who cares deeply for both Billy and Emmett. I think she represents a type of kindness that’s been almost non-existent for Billy or Emmett. Sally turns out to be a bold and wise character—she bristles at the strictures placed on women in 1950s America and has what it takes to overcome them. We don’t know if she and Emmett fall in love; Towles doesn’t give his story such a tidy narrative. But I suspect most readers will hope they end up that way.

I definitely finished Lincoln Highway hoping that Towles is busy writing his next novel. It almost doesn’t matter what time or place he decides to write about. I just know I’ll want to read it.